Zion National Monument Utah to Barrie Ontario

There’s no place like home . . .

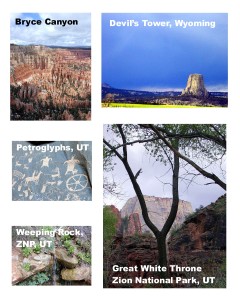

June 15, 2003Following the Easter weekend and the celebration of my 50th birthday, I figured I had about 6 weeks to make the journey from Page, Arizona to Barrie, Ontario for my new job. Before heading north, I consulted my two guide books, Courtney Milne’s Spirit of the Land and Colin Wilson’s Atlas of Holy Place and Sacred Sites, in order to determine the places I would visit en route. My first stop was at Zion National Park in southwestern Utah. This park was originally named “Mukuntuweap,” a Paiute Indian word for straight canyon. Shortly after it opened, however, it was renamed “Zion” to reflect the Mormon sense that it was the Heavenly City of God. The names of the sites within the park honour the Native and Mormon sacredness of the place. For instance, the Temple of Sinawava, the Paiute Wolf God, is at the head of the canyon. Other rock formations have names like the Great White Throne and the Court of the Patriarchs. In an effort to reduce traffic congestion and the resulting ecological impact, vehicle traffic is not allowed throughout most of the park. Instead, there is a free shuttle bus. Unfortunately, the weather was cold and rainy, and on several occasions, the rain turned to snow. Nevertheless, I enjoyed the day and didn’t get too wet. From Zion, I travelled to Bryce Canyon, the place of the legend people. Courtney Milne shares this story about Bryce Canyon:

The Paiute Indians who lived here gave it a name that translates to “red rocks standing like men in a bowl-shaped canyon.” According to a Paiute story, before there were any Indians, this place was inhabited by Legend People called To-when-an-ung-wa, who looked partly like people and partly like birds, animals, or reptiles. For some reason, the Legend People in that place were bad, so Coyote turned them all into rocks. You can see them now, some standing in rows, some sitting down, some holding onto others, their faces painted just as they were before they became rocks (120).

For those who receive the photo version of the travelogue, you will be able to see the rock people of the legend. Again, the weather was unusually cold with more snow.

My next three stops were to experience Native rock art–petroglyphs at Capitol Reef National Monument, on the cliffs along the Colorado River near Moab, and Newspaper Rock, all in Utah. From here, I crossed into Colorado to visit the Anasazi Heritage Center in Dolores, Colorado, which had an interesting video presentation and a special exhibit on Native weaving. Mesa Verde National Park was a special highlight of my visit to southwestern Colorado. Like Chaco Canyon and Canyon de Chelly, the area encompassing Mesa Verde was once inhabited by the Anasazi. I visited the museum, which had many exhibits illustrating the stages of human life in the area. I also hiked a rather strenuous trail to view another set of petroglyphs. I stopped several times along the trail to revel in the extraordinary beauty of the canyons and the burgeoning of spring.

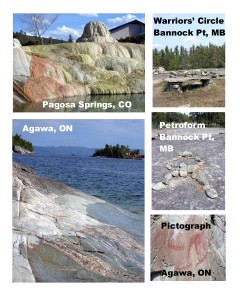

My next destination was Pagosa Springs, which gets its name from the Paiute word for “boiling waters.” Courtney Milne shares a Ute story about a time of plague, when even the medicine people could not stop the deaths. A tribal council built a giant bonfire, then danced and beseeched the gods for help. They slept, and when they awoke, the bonfire had been replaced with a pool of boiling water, a gift from the Great Spirit who healed them of their sickness (84). In many ways, Pagosa is similar to Manitou Springs in Saskatchewan. They are both holy places connected with healing, and they are places where warring tribes co-existed in peace. Today, the springs consist of a number of smaller pools at varying temperatures. There is even a pool in the San Juan river, which was at about 46 degrees (F) on the day I visited. Now THAT was refreshing!

As I continued from Salida to Colorado Springs, the highway followed the Arkansas River. The day was resplendent with sunshine, and I saw dozens of fly-fishermen trying their luck. I longed to be able to pull old Buckskin off the road to join them, but I haven’t learned how to fly fish yet. One of my goals for this coming summer is to learn and practice this sport so I can, with some luck, capture a fresh fish for my dinner. Unfortunately, the rain and cold had returned by the time I arrived at the Garden of the Gods in Manitou Springs near Colorado Springs. The beauty of the rock formations would have been enhanced by better light conditions.

From Colorado Springs, I began the northward trek–the song “Alberta-bound” in my mind. Along the way north, I made two stops. First, I visited Devils Tower National Monument in Wyoming. Known as “Mateo Tepee” to many Native Americans, Devils Tower is a teardrop- shaped core of an ancient volcano. There are a number of Indian legends that describe how this mass of land came to be. Here is a Cheyenne version of the story:

There were seven brothers. One day when the wife of the oldest brother went out to fix the smoke wings of her tipi, a big bear carried her off to his cave. The man mourned her loss greatly, and would go out and cry defiantly to the bear.

The youngest brother, who had great power, then told the oldest one to make a bow and four blunt arrows. Two arrows were to be painted red and set with eagle feathers; the other two were to be painted black and set with buzzard feathers. The youngest brother then took the bow and the four arrows, told the other brothers to fill their quivers with arrows, and they all set out after the big bear.

At the cave, the youngest brother told his brothers to sit down and wait. Then he turned himself into a gopher and dug a big hole to the bear’s den. He crawled in, and found the bear lying with its head in the woman’s lap. The young Indian put the bear to sleep, and changed himself back into an Indian. He then told the woman that her man was mourning and that he had come to take her back. He told her to make a pillow of her blanket and put it under the bear’s head. Then he had her crawl backwards through the hole he had dug. So he got her out to where the six brothers were waiting. Then the hole closed up.

The woman now told the brothers they should hurry away, as arrows would not go into this bear. After they had all gone the bear woke up, went out of his den, and walked around it. He found the trail of the Indians. He started after them, taking with him all the bears of which he was leader.

The youngest brother, with the four arrows, kept looking back. Soon they came to the place where Bear Lodge now stands. The youngest boy always carried a little rock in his hand. He told the six brothers and the woman to close their eyes. He sang a song and finished it. When the others opened their eyes the rock had grown. He sang four times, and when he had finished the rock was just as high as it is today. This the younger brother could do because he was a holy man.

When the bears reached Bear Lodge, they all sat down in a line, but the leader stood out in front. He called, “Let my wife come down!” The young Indian mocked the bear, saying that he might be a holy being but that he couldn’t get her.

Then the brothers killed all of the bears except the leader. It growled and kept jumping high up the rock. His claws made the marks that are on the rock today. While he was doing this, the youngest brother shot the black arrows at him. They did not hurt him, and by taking a run, the bear went further with every jump. The third time he jumped the young Indian shot a red arrow at him, but it did not enter the bear. At the fourth jump the bear almost got up on the Tower. The young Indian then shot his last arrow. It went into the top of the bear’s head and came out below his jaw and the bear fell dead. The youngest brother then made a noise like a bald eagle, and four eagles came. They took hold of the eagles’ legs and were carried down to the ground.

Now the young Indian told his brothers to pack in wood and pile it on top of the body of the bear leader. This was set on fire. When the bear got hot it burst, and small pieces, like beads of different colors, flew off. The younger brother told the rest to put these back in the fire with a stick. (If they had picked up these pieces with their hands the bear would have come to life again). Finally, the bear was burned to ashes.

After this, there were a great many young bears running around. The Indians killed all but two. The younger brother told these two not to bother the people any more, and he cut off their ears and tails. That is why bears have short ears and no tails to this day.

Looking at the rock formation, it was easy to imagine the claws of the legendary bear gouging the sides of Devils Tower. As I have travelled, I have learned how such sacred geography often plays a vital role in the traditional stories that communicate the relationship between the Creator, the land, and the people. As the spiritual beliefs of the people become intertwined with the landscape, these sites become hallowed, places where the spiritual realm of the Creator mingles with the physical realm of the creature.

My next stop was at Pictograph Cave near Billings, Montana. During this time, I noticed that Buckskin had developed a slow leak from the radiator. While the van was not overheating, I still wanted to get this problem checked out and repaired as soon as possible, so following my visit to see the rock art, I headed north to return to Canada.

How can I describe the wonderful sense of homecoming that accompanied my crossing of the border? In spite of the snow, it was great to be back on Canadian soil. Like Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz says, “there’s no place like home.” During my US adventure, I found myself missing several uniquely Canadian institutions–the CBC, Canadian Tire, Tim Horton’s! So as soon as I crossed the border, I tuned in the CBC, and then, in Lethbridge, pulled into “Timmy’s” for soup, coffee, and, of course, a doughnut. What bliss! As I turned into the local Walmart to spend the night, I remembered being there some 7 months earlier with Buster. It was a bittersweet moment. The following day, I arrived on the doorstep of my cousin, Colleen, in Calgary (the one whose wedding I officiated 7 months earlier). The next day, Buckskin spent the day in the car spa, getting a new radiator and a new starter.

While in Calgary, I visited several cousins, and I stopped in at Rostad Tours to begin planning my next travel adventure–a spiritual pilgrimage to Scotland in September 2004. This will be a tour I will host for up to 30 pilgrims who are interested in visiting sacred sites throughout Scotland (including Iona, Skye, Findhorn, Culloden, Edinburgh, Lindisfarne, and others). If you are interested in accompanying me on this adventure, just let me know and I will forward the information.

The next part of my journey took me through Edmonton, Wainwright, Saskatoon, and Regina. In each place, I was able to visit many of my friends, although I didn’t get to see everyone. Once the details of the move from Regina to Barrie were complete, I set back out for the final leg of the journey. Along my route, there were three locations of special interest to me. First, I stopped in White Shell Provincial Park to see the petroforms at Bannock Point. Petroforms are another type of rock art and consist of rock placed on the ground in certain shapes. As luck would have it, I visited the site just as a Native elder was hosting a tour for a small group of American visitors, and they invited me to join them. After the others left, the elder and I returned to enjoy the sunset from within a rock formation known as the warriors’ circle. The elder is Midewewin, a healing society within the Anishinabe, and he had many stories of healing to share. Together, we smoked a pipe of Kinnikinnick. It was a very special moment for me. The second sacred site on this final leg of my journey was another rock art site–the pictographs at Agawa along the shore of Lake Superior near Wawa. To access this site, one must creep out along a rock platform at the water’s edge, while clinging to a rope. The view is spectacular, although the pictographs are probably better viewed from a boat. After months of living in the desert, my soul drank in the lusciousness of the trees, rocks, and water so characteristic of the Canadian shield. The smell of pines and sun-baked rock always reminds me of childhood summer holidays spent in the north of Ontario. The third sacred site was Manitoulin Island. According to the Anishanabe, the entire island is sacred. It is said that Gitchi Manitou (the Great Spirit) still visits to this day. My campsite for the night was on the shore of Manitouwaning Bay, known also as “the den of the Great Spirit.” That night, I delighted to hear a symphony of loons and wolves. The next day, I visited the art gallery and museum at the Ojibway Cultural Centre in M’Chigeeng. It was here I found a quote from a Native Elder that helped me tie together my experience of the rock art I had seen during my journey:

The art and craft work of the Indian people is that of the land we live on. It is alive, distinctive and real, indicative of the people. The arts and crafts are founded on a spiritual culture as enduring as the earth. Indian people have no word for art. Art is part of life, like hunting, fishing, growing food, marrying and having children, this is art in its broadest sense–an object of daily usefulness, to be admired and appreciated, nurturing the needs of both soul and body, thereby giving meaning to everything. –Mary Lou Fox Radulovich

My last stop before heading to Barrie and my new job was at Riverside Lodge in Sturgeon Falls, the home of my father, brother, sister-in-law, and nephews. Ever since my brother, Wayne, could speak, he dreamed of owning a fishing lodge, and 18 years ago his dream (and occasionally, his nightmare) came true. The question, “Where are you from?” for me is difficult. To the best of my ability, I try to make my home wherever I am. Although Riverside Lodge has never been my home, as such, much of my family energy is concentrated in this place. As the river of time flows, many landmark celebrations have lodged here: the 40th wedding anniversary of mom and dad; the wedding of my brother, Wayne, and sister-in-law, Brenda; the memorial service for my mother, whose ashes were placed in Lake Nipissing near her favourite fishing spot. In many ways, this lodge is sacred for me. Brian Maracle, who writes an introduction in Courtney Milne’s book, The Spirit of the Land, has helped me understand how this can be:

. . . all places are sacred. The places we thank the Creator. The places the spirits live. The places we celebrate our ceremonies. The places we seek visions. The places we bury our dead. The places we name our children. The places we get our food. The places we gather our medicines. The places we greet the morning sun. The places we welcome the spring. The places we seek out for healing, contemplation and rejuvenation. All of the land on Great Turtle Island is hallowed ground because all of our activities are part of the sacred cycle of life (Milne 10-11).

On June 2, having travelled over 35,000 miles (not kilometers), Buckskin and I headed south from North Bay for the final stretch of the journey. Although I lived in CFB Borden (15 minutes west of Barrie) from 1986-1989, the area has changed dramatically. Situated only 45 minutes north of Toronto, Barrie has become a bedroom community for the mega-metropolis. As I cruised around the city, several qualities stood out in stark contrast to the peaceful lifestyle of Buckskin and the desert:

- the busyness of its inhabitants and the speed at which they drive

- the noise

- the vast amount of space dedicated to retail businesses

- the squadrons of earth-moving equipment, evidence of further population growth and expansion.

Soon after arriving and reacquainting myself with the major roads, I began the search for accommodation. As luck would have it, I found a beautiful apartment in the country. My new home is located amidst lush farms and at night, I can hear cows lowing. In the morning, I often hear the chickens from the next door neighbour’s coop. Lake Simcoe is a short walk from here, and there is a golf course in the backyard. The apartment is attached to a large house, owned by a young couple who work in Toronto. Simcoe, their dog, and I have become good buddies. The place is surrounded by mature trees, and I can bird-watch from my own deck. I have the luxury of large windows that open in four directions. There is also a sky light in the bathroom! It is a delightful place to live–filled with peace and light.

As I reflect on the J/journey that is, for this time, complete, I find the words of W. Paul Jones helpful. In his book, A Table in the Desert: Making Space Holy, he shares this wisdom about the solitude of the pilgrim:

There have always been persons who by temperament or situation are alone in the midst of people, without understanding why. They might be recluses, in one way or another. But there are others who, living active and rigorous lives in the world, leave it all behind and go into the “desert.” Such a hermit vocation is not usually for the young, for it dare not spring from undue idealism or rebellion. There comes a time when one simply becomes tired of pretenses and games. A thirst for integrity takes over, a passion to undertake the austerity of living in simple honesty, without convenience, support, or distraction. This call into solitude is a pilgrimage into darkness and crucifixion, for it annihilates the self one once knew and fostered. It is a lonely path, hidden from the eyes of the world, which neither knows nor cares.

In any case, the world is certain that the hermit is a failure. Free from the lure of possessions, power, and status, the contemplative life has no practical use or purpose. Hermits are pilgrims, dependent on pure faith–faith that this is where God would have them be. To walk into such silence is to be stripped of certainty that one has an answer to anything–until the questions that once plagued the mind nestle in one’s soul as friends. One would hardly enter such a valley of shadows willingly. Yet amidst all the options one has, strangely there is no choice. Nothing else matters except to be a person of prayer. And some day, in the gentle quietness, standing among the ashes of dreams and ambition, one may be blessed with the only certitude likely to be given: that to seek is to be sought, and to find is to have been found.

To be drawn into such solitude is really an invitation to share the companionship of God’s loneliness–the God emptied in total identification with us–ignored, hidden, forgotten, and profoundly poor . . . What the “hermitage of the heart” is about is the establishment of a “soul” . . . So the hermit is a model for leaving both memories and plans aside, content to be a guest in the quietly throbbing present (67-69).

Could it be that when I felt the most lonely, I was closest to God? Is my deep yearning for companionship a reflection of how God feels?

As I prepare once again to embrace an active and rigorous life in the world, I carry with me a remarkable gift from my time away in the desert–an acquaintance with the holy that dwells within my body–my soul. I give thanks for the opportunity to have been “a guest in the quietly throbbing present.” As I continue my Journey through this adventure we call life, may the stillness I found in the desert continue with me into this more complex place filled with convenience, support, and distraction.

Sarah York, in her book Pilgrim Heart: The Inner Journey Home, says that “the goal of any sacred journey, physical or metaphysical, is to feel more at home at home. Our task once we have returned is to imbue our everyday lives with a sense of grounding in our spiritual understandings–in those gifts of holy wisdom that have taught us how to be more at home no matter where we are (172).” This past weekend, I took part in a “home tour” organized by the local church. Six extraordinary homes in the area were “open” to visitors. At the end of the tour, a woman turned and asked me which home I liked the best. My response caught me off guard. “I have to admit they are all beautiful,” I said, “but the one I like the best is the little apartment where I awoke this morning.” Home. For now…

References

Jones, W. Paul. A Table in the Desert: Making Space Holy. Brewster, Massachusetts: Paraclete Press, 2001.

Milne, Courtney. Spirit of the Land: Sacred Places in Native North America. Toronto: Viking, 1994.

Wilson, Colin. Atlas of Holy Places & Sacred Sites. New York: DK Publishing, 1996.

York, Sarah. Pilgrim Heart: The Inner Journey Home. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001.

Backyard at Gilford.

Red squirrel in bird feeder at Gilford. “Can we get Internet out here?”

Simcoe.

First snow on deck in Gilford.

Christmas table in Gilford (2003).